During the late 13th century CE king Philip IV curbed the power of Guy of Dampiere, count of Flanders,

trying to add the rich and populous county to his own territory.

Guy fought back and in 1297 CE allied himself with England, enemy of France.

But the French struck back and defeated his forces in several battles, progressively occupying the county.

The common people suffered from heavy taxes.

In 1302 CE, in fits and starts, a rebellion got underway, which quickly gained momentum.

In response, the French king sent an army into Flanders under Count Robert II of Artois.

It consisted of 2,500 knights and squires, 1,000 crossbowmen, 1,000 spearmen and 3,500 light troops.

It was a classic Medieval army, the core being the knightly cavalry.

The Flemish countered with city militias: 3,000 men from Bruges, 2,500 from the west, 2,500 from the east and 1,000 from Ypres.

About 400 of these were nobles, the rest commoners.

Almost all of them were organized by guild and fought as infantry.

They were armed with pikes, "goedendags" (large spiked clubs), bows and crossbows; armor varied.

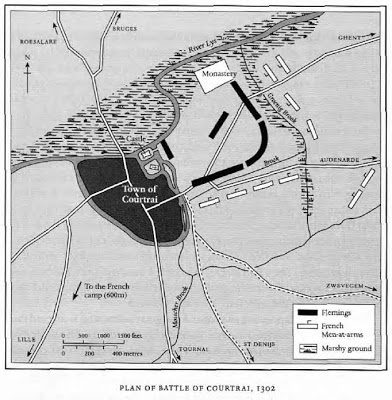

The Flemish blocked the French advance at Kortrijk, shielding Ghent, Bruges and Ypres together.

Robert attacked the town gates for three days, without success.

On the next day he found the Flemish army entrenched to the northwest of the town, shielded by the river Lys and the Great Brook.

The waterways were serious obstacles to attack, but also prevented any quick retreat.

The tactical position reflected the strategic one; the citizens of the cities could expect widespread plunder and killings if they lost the battle.

The Flemish leaders instructed the men to stand fast, kill both men and horses, take no prisoners and to refrain from looting.

Around noon, the French started to try to draw the Flemish out with crossbow fire, but they had retreated as far away from the brook as possible to minimize the damage.

When the crossbowmen got closer, Robert recalled them, fearing a counterattack by the Flemish heavy infantry.

Then he ordered his cavalry forward.

They caused some damage to the retreating crossbowmen and then struggled to cross the brooks, but managed it without too much trouble.

They did however lose their momentum and lacked enough distance to build up full speed again.

Nonetheless they charged with confidence.

To their surprise the Flemish ranks did not break.

The knights managed to pierce the enemy formation at a few points, but could not shatter it.

A vast melee ensued, where pikes and goedendags caused heavy damage.

In the meanwhile the French garrison in the castle at Kortrijk tried to break out, but was contained by the townspeople.

The Flemish recovered and launched a counterattack, threatening to crush the knights between them and the brooks.

Robert personally led his reserve in an attempt to reverse the situation.

However his horse was killed and then he himself perished too.

The Flemish finished off the remaining knights, then crossed the waters and attacked the French rearguard.

Some Brabançons who fought with the French tried to change sides, but that move came too late; they were killed.

The French forces fled in panic and after three hours the battle was over.

The French losses were at least 1,000, many of them knights; the Flemish lost only 100 men.

The Battle of the Golden Spurs was an example and inspiration to other peoples.

They had shown that ordinary men could defeat knights.

Others followed: Scottish pikemen defeated English knights; the Swiss gained their independence from the Holy Roman Empire;

Bohemian Hussites developed new tactics using wagons.

Meanwhile the Flemish were not yet done with the French and would fight many more battles with them in later years, sometimes winning, sometimes losing.

War Matrix - Battle of the Golden Spurs

Late Middle Age 1300 CE - 1480 CE, Battles and sieges